I have been working with a microservices application using gRPC as the main service-to-service communication mechanism for almost a year. So, I decided to write a blog post and share my experience on how to do gRPC right in a microservices world! So, let’s get started!

TL;DR

- DRY! Have a package for your common messages.

- Choose unique names for your gRPC packages.

- Choose singular names for your gRPC packages.

- Distinguish your gRPC package names with a prefix or suffix.

- Implement health check probes as HTTP endpoints.

- Use a service mesh for load balancing gRPC requests.

- Centralize your gRPC service definitions in a single repo.

- Automate updating of your gRPC tools and dependencies.

- Automate generation of source codes and other artifacts.

Microservices

Defining what microservices architecture is and whether you need to adopt it or not are beyond the scope of this post. Unfortunately, the term microservices has become one of those buzz words these days. Microservices is neither about the number of microservices, different programming languages, nor your API paradigms! In essence, microservices architecture is Software-as-as-Service done right!

The most import thing to get microservices right is the concept of service contract. A service contract is an API that a given service exposes through an API paradigm (REST, RPC, GraphQL, etc.). In the microservices world, the only way for microservices to communicate and share data is through their APIs. A microservice is solely the source of truth for a bounded context or resource that it owns. A service should not break its API (contract) since other services rely on that. Any change to the current major version of API should be backward-compatible. Breaking changes should be introduced in a new major version of that service (technically a new service).

One important implication of microservices architecture is the organizational change that it requires and introduces! The same way that microservices are small, independent, and self-sufficient, the same way they can use different technologies and follow different development workflows and release cycles. Each microservice can be owned by a very small team. Different teams (microservices) can adopt slightly different practices (coding style, dependency management, etc.) as far as they do not break their commitment (service contract or API) to other teams (other microservices).

gRPC

gRPC is an RPC API paradigm for service-to-service communications. You can implement and expose your service API (contract) using gRPC. Thanks to grpc-web project, you can now make gRPC calls from your web application too. Topics like the comparison between gRPC and REST or whether you need to implement your service API as gRPC are again out of the scope of this post.

gRPC itself is heavily based on Protocol Buffers. Protocol Buffers are a cross-platform language-agnostic standard for serializing and deserializing structured data. So, instead of sending plaintext JSON or XML data over the network, you will send and receive highly optimized and compacted bytes of data. Version 1 of Protocol Buffers has been used internally at Google for many years. Since version 2, Protocol Buffers are publicly available. The latest and recommended version of Protocol Buffers is version 3.

gRPC uses Protocol Buffers to define service contracts. Each service definition specifies a number of methods with expected input and output messages. Using gRPC libraries available for major programming languages, these gRPC protocol buffers can be implemented both as server or client. For compiled programming languages like Go, source codes need to be generated using Protocol Buffers Compiler (protoc) ahead of time.

Architecture

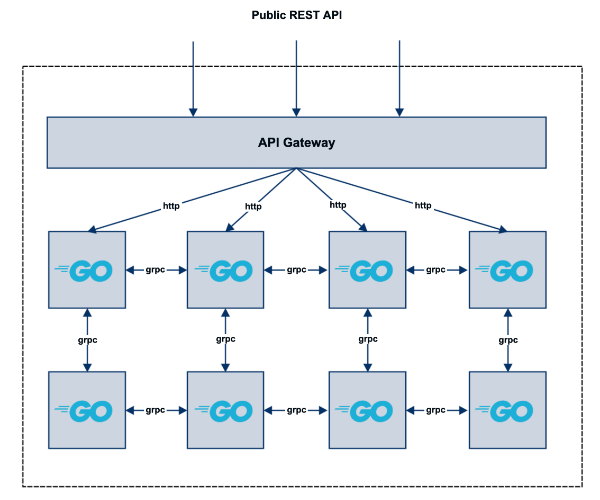

The Microservices architecture I have been working on consists of roughly 40 microservices all written in Go and containerized using Docker. Since Go is a compiled and statically typed language, all gRPC/protobuf definitions should be compiled and source codes should be generated in advance. An API gateway receives HTTP RESTful requests and backend communications are done through gRPC calls between different microservices.

Challenges

Health Check

One immediate question for a service that only talks gRPC is how do we implement health check? Or if you are using Kubernetes as your container platform, how do we implement liveness and readiness probes?

To this end, we have two options:

- Defining and implementing the health check probes as gRPC calls.

- Starting an HTTP server on a different port and implementing health check probes as HTTP endpoints.

Implementing the health check as HTTP is straightforward. All external systems can easily work with HTTP health checks. However, setting up a separate HTTP server requires some coordination with gRPC server to ensure that the gRPC server can successfully serve the requests.

Implementing the health check as another gRPC method is not a challenge itself, but getting the external systems (AWS load balancer, Kubernetes, etc.) to talk to it is the challenging part. This approach has a better semantic since every gRPC service comes with health check and the health check itself is a gRPC request.

Here are some useful resources on this topic:

Load Balancing

Here is another interesting challenge! How do we do load balancing for services talking gRPC? For answering this question, we need to remember how gRPC is working under the hood.

gRPC is built on top of HTTP/2 and HTTP/2 uses long-lived TCP connections. For gRPC this means that an instance of gRPC client will open a TCP connection to an instance of a gRPC server, sends the requests to and receives the responses from the same connection, and it keeps the connection open until the connection is closed. Requests are multiplexed over the same connection. This is a big performance improvement since we do not need to go through the overhead of establishing a tcp connection for every request. However, this also means that the requests cannot be load-balanced in the transport layer (L3/L4). Instead, we need to load balance gRPC requests in the application layer (L7).

For this purpose, a load balancer component needs to open a long-lived connection per instance, retrieves enough information from Protocol Buffers data being transferred, and then it can load balance gRPC requests.

Needless to say, you should not implement an ad-hoc load balancer for your gRPC requests. You should rather use a solution that works for supported programming languages and platforms and addresses additional requirements such as observability.

Some resources worth reading:

Dependency Management

Dependency management is another important topic for maintaining microservices in general.

gRPC community has done a great job maintaining backward-compatibility between different versions Protocol Buffers compiler (protoc).

This has been one of the key factors in making gRPC a successful RPC protocol.

protoc plugin for generating Go source codes also has done a good job maintaining backward-compatibility among different versions of protoc and go.

However, from time to time we may see some breaking changes are introduced (of course for a reason).

One example I can think of was the introduction of XXX_ fields for generated structs in Go

(#276, #607).

As a result, if you do not update your gRPC toolchain reguarly, updating them for getting new features and performance improvements in the future will become harder. In the worst case, you may be stuck with using specific old versions of your gRPC compiler and plugins.

Centralize or Decentralize Protocol Buffers Management?

This is another interesting topic since it may not look an important decision. When it comes to managing your gRPC Protocol Buffers and generated files, you have two options:

- Keep Protocol Buffers and generated files on the same repo as the owner microservice (decentralized)

- Centralizing all Protocol Buffers and generated files in one mono repo.

If you think of HTTP-based APIs such as REST, you define your HTTP endpoints per repo. Basically, each repo owns all the definitions regarding its HTTP APIs. This is absolutely a best practice (self-sufficient repos) and complies with Microservices philosophy (self-sufficiency).

Similarly, it also makes sense for gRPC service definitions to live inside their own repos. The repo that implements the gRPC server for a given gRPC service, owns the gRPC service definitions alongside the corresponding generated source codes (if required). Other repos that want to consume a given gRPC service, import the grpc package from the owner (server) repo.

So far so good, right? But, there is one important difference especially for compiled programming languages. HTTP protocol is very established and it is very hard to imagine that suddenly something about HTTP changes. For gRPC and Protocol Buffers to work, a middleware layer for marshalling and unmarshalling is required. Furthermore, compiled programming languages require source codes be generated using Protocol Buffer compiler and language-specific plugins.

For this purpose, we need to make sure that gRPC source codes are generated in the pipeline as the artifacts of builds using the same versions of protoc, protoc plugins, and other tools.

If you have a central pipeline, you only need to implement this functionality in one place and updating the functionality requires changes only in one place.

If you have a repo per microservice and your pipeline is a yaml file in each repo,

then you need to implement a modular pipeline in which you import the functionality for generating gRPC source codes from a single source of truth.

If building a modular pipeline is not a straightforward task, you can centralize all of your gRPC services and their generated codes in a mono repo. In the pipeline or build job for this repo, you can use the same versions of all tools you need to generate gRPC source codes and other files. At minimum, you can re-generate the gRPC source codes and other files in your build job and make sure there is no difference between those files and the files checked in by developers.

Lessons Learnt

1. DRY

Don’t repeat yourself! If you have a common message that you need it in multiple service definitions, you can define it in a separate package and import it in your service definitions.

For example, if you are implementing health checks as gRPC requests, you can define request and response messages for health check method in a common package.

2. Use Unique and Consistent Package Names

The name of a package is part of your gRPC service definition. This means changing the name of a package will break that gRPC service definition.

Choosing a package name for your gRPC service definition can be a bit different depending on the target programming language. You need to make sure that your package names follow the conventions for your programming languages and are consistent with your other gRPC package names.

- Choose unique names for your gRPC packages

- Choose singular names for your gRPC packages

- Distinguish your gRPC package names with a prefix or suffix (In Go, you can use

PBsuffix for example)

3. Implement Health Check Probes as HTTP

HTTP health checks (including Kubernetes liveness and readiness probes) can be consumed easily by all external systems. So, this way you do not need to get a gRPC client to check your service health and your service implementation is more future-proof (You can still have a health check method on your gRPC service and your http health check handler makes a call to it).

4. Use a Service Mesh for Load Balancing

For loading balancing gRPC requests, use a service mesh. All major service meshes (Linkerd, Istio, and Consul) supports L7 load balancing for gRPC. Service meshes also provide observability capabilities for your gRPC calls such as metrics and tracing.

5. Centralize Your gRPC Protocol Buffers

From our experience, centralizing all gRPC service definitions in one repo works better than keeping service definitions per repo. You can use the same version (ideally always the latest versions) of protoc, protoc plugins, and other tools for generating source codes for all of your service definitions. You can also make sure all of your gRPC service definitions are consistent with respect to naming, formatting, documentation, and other conventions.

It is worth mentioning that all of these qualities are also achievable with per repo setup by employing enough automation and tooling.

Ideally, you should not have any breaking change in your gRPC service definitions. But, if for any reason you need to do so, centralizing your service definitions in one repo allows you to semantically version all of your service definitions together. So, you do not need to know which version of a given package is working with which version of another package.

6. Automate Code Generation For gRPC

Do not trust your developers to generate the source codes for your gRPC service definitions! You don’t want every developer to generate source codes with their own versions of locally installed gRPC tools every time they make a change. Remember! Everything that can be automated, must be automated.

In your pipeline you should lint your service definitions, and generate source codes and other artifacts for your service definitions as part of your build process.

7. Automate Your Dependency Management

Automating dependency management is a best practice and is not specific to gRPC. Depending on the target programming language, gRPC needs other libraries to work. Make sure you automate updating your tools and dependencies for both generating source codes and runtime.